It’s one of the frustrations of the kidney shortage that many people want to donate a kidney to a loved one but can’t, because their blood type is not compatible with their intended recipient. If they donated, their kidney would be rejected.

In the past, living donors who did not match their recipients simply couldn’t donate at all. The failure to realize those donations was – and is – a true loss of potential kidneys for patients in need. Paired kidney donation was designed as a solution to this dilemma, and this innovative system has made strides in reducing the kidney donor shortage by allowing more people to donate regardless if they match their prospective recipient – in exchange for their loved one getting a kidney from someone else.

Unfortunately, too many patients and their families don’t know about paired donation, don’t understand it, or don’t trust it. The UCLA Transplant Research and Education Center(TREC) and the National Kidney Registry(NKR), with support from the Terasaki Research Institute(TRI) and Health Literacy Media(HLM), are researching ways to educate harder-to-reach patients and potential living kidney donors about paired donation, address disparities in access to transplant education, and standardize effective transplant education. UCLA recently was awarded a $1.2 million grant from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration(HRSA) to conduct this research in collaboration with the National Kidney Registry.

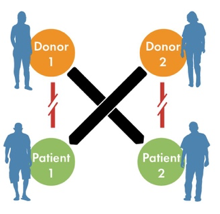

What is paired kidney donation? Paired donation enables donor-recipient pairs, or chains of pairs, to swap incompatible kidneys for compatible ones. Drawing on some of the best minds in medicine, data analysis, and health services, the system employs sophisticated algorithms to sort the antigen profiles, blood types, and other bio-data of potential donors and kidney patients to match donors and recipients; once a patient is matched, paired-donation networks, including the National Kidney Registry, coordinate surgery, transportation of organs, and cooperation among hospitals. The system is based on the principle that many people will donate a kidney to a stranger if it means the donor’s loved one will get a kidney from a compatible donor.

The system was first tested in South Korea in the 1990s. In 2000 the first paired donation transplants took place in the United States. The early years of the system in the U.S. saw numerous paired-donation programs established, most working in siloes, which meant smaller donor pools and limited geographical reach. The National Kidney Registry, a nonprofit private agency, was founded in 2008 to make the system more robust by connecting transplant centers, broadening the pool of participants, and refining the analytics used to sort donor and recipient bio-data. In the 10 years since its founding, NKR has become a leader in developing paired donation, bringing transplant centers together by creating a large network of transplant providers with centralized data, creating systems for sharing and cooperation, coordinating transplant chains, and addressing the ethics of centers’ participation. There are now 80 transplant centers working with NKR, which alone has coordinated almost 3,000 transplants. TREC’s director, Dr. Amy Waterman, serves as NKR’s director of research to support collaborative research opportunities to advance the field.

Paired donation is already reducing the organ-donor shortage and allowing for transplants to be more precisely tailored. Transplant surgeon Jeffrey Veale, MD, of the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, points out improved quality of the matches possible within a paired-donation system. Given the diversity of blood type and other biological characteristics of potential donors participating in the system, as well as the software that can match donors and recipients, it is now possible to optimize closer matches for patients. Before paired donation, this was not possible. According to NKR founder Garet Hil, the number of unmatched kidney patients in the Registry is down to 2%.

The challenge to expanding paired donation is that it’s difficult for people to trust a system they don’t understand. As the system becomes more sophisticated and more complex, culturally competent information about paired kidney donation’s benefits, risks, and how to participate is needed – for patients, potential donors, and dialysis care providers. Transplant and dialysis centers across the nation need better information about how kidneys are matched and shipped.

To address the need for better educational resources in paired donation, TREC and NKR have formed a collaborative, which includes TREC’s partners Health Literacy Media and the Terasaki Research Institute. The HRSA grant will enable the collaborative to develop and test the value of new paired-donation educational materials at 20 of NKR’s network of 80 transplant centers. Ultimately, the protocols and materials will be used at all of NKR’s centers, and possibly beyond.

If easy-to-access, effective, consistent education about paired donation were available to more patients and members of their communities, more people would learn about what it has to offer and the rate of kidney patients receiving transplants could, potentially, increase exponentially over time. Long waiting times on deceased-donor waiting lists could be less of a concern. More people would face end-stage renal disease – either their own or in a friend or family member – better equipped to make informed, timely decisions about paired donation, better equipped to make decisions that are right for them. Fewer would die while waiting for a kidney.