Dear Readers,

People always ask me why I work in the field of transplant. I took a memoir writing course where I wrote a piece about the moment I fell in love with this field. I was 28 years old.

– Amy Waterman

I got an email from the kidney surgeon that morning. The note was direct: “Transplant surgery tomorrow. Need permission from the family to observe. Meet me at 4 pm.”

I left my office and walked to the Transplant Center. I didn’t know that I would be meeting patients beforehand, so I hadn’t dressed right for this occasion. Where was my lab coat, my badge? Instead, a glimpse of pale lavender tights peeked out between my floral skirt and brown boots. The kid caught wearing a pink tutu to school.

Twenty minutes later, the surgeon rounded the corner and gestured for me to come into a patient’s room. I didn’t really like this guy. Three years ago, he had yelled at me in this same hall so loudly that the nurses in the main bay couldn’t look me in the eye afterward.

He yelled at me because I was running a research study for potential living kidney donors. One of the questions was whether the donors wanted, or needed any money to cover the costs of childcare, time off work, or lost wages. I was asking them, in the survey, how much they needed.

“Those donors are going to think that we will pay them to donate!” “That’s illegal.” His words were a punch to the soft part of my stomach. My research ethics as a psychologist, challenged. My eyes burned and I blinked quickly to avoid tears. The elevator doors opened and closed as new patients arriving for their transplant appointments witnessed my pink face.

Be logical, rational, calm, I thought to myself. “Sir, during the research study, I told them that they wouldn’t be offered money as part of receiving their healthcare here.” I said. And I got permission from the administrator of the transplant center.

“But you didn’t ask me,” was all he said before he left.

I didn’t sleep that night, wondering if my research and education program would be shut down. A surgeon is the king of the transplant kingdom, and if he complained, I might lose access to patients to conduct my research all together. My brain whirled. I wondered if I would have to move out of the city altogether. Or find another research topic. I stopped the study and never published anything about reimbursing donor costs.

Now we were together again, walking into Room 1503. Near the door, an older African-American woman sat in one bed, looking small and scared. A twenty-something boy played a handheld video game in the other bed beside the window. His extreme thinness registered immediately. Two other men were in the room, one burly man sitting in a chair that looked too small for him and another speaking to the woman. The surgeon explained to me that, tomorrow, the woman in the bed was donating her kidney to her son.

The doctor told the family that I was making a transplant video to help patients learn about their options. I asked the woman if it was ok to film their donation and surgery tomorrow. Her husband standing beside her asked if I could send them a copy of the two surgeries on film. I agreed.

The mom signed the permission forms without speaking. I smiled at her, trying to be reassuring. As I handed the son the clipboard with the paperwork to sign, I wanted to pull him aside. I wanted to say to him, privately that with a transplant, he could have more freedom to get away from his parents. And, stop feeling so sick. But the boy didn’t look up. “The doctor is very good,” was all I said.

As we walked back down the hall, the surgeon told me that the big guy sitting in the chair was a famous football player. He pulled out his phone to show me a picture someone had taken of the two of them earlier, the surgeon overshadowed by the football player twice his size. I smiled as if knew who the football player was and cared, neither of which was true.

“I will see you at 6 am tomorrow,” he said, and we went our separate ways.

The next morning at 5 am, I decided that observing a kidney surgery was a really bad idea. I never watch horror movies. I couldn’t even remove a splinter from my niece’s finger that she got climbing over a fence. It isn’t about the blood. It’s about too much empathy. These people aren’t ok. They are in pain. I worry too much.

But, the surgeon is expecting me, as is the videographer. So, off I went, slightly nauseated. In the changing room, the videographer and I dressed in green scrubs and stood outside the room where the kidney patient was getting prepped for surgery. The mother’s donation surgery already started in the operating room next door.

Through a small window in the door, I start feeling very light-headed. “You aren’t going to pass out on me, are you,” the surgeon had asked me before agreeing to let us film the surgery. I promised him that I wouldn’t, but, now, I began to regret my vow. I felt woozy and the layers of scrubs felt claustrophobic. I took deep breaths to calm myself.

The operating room doors swung open and the surgeon appeared, gloved and masked. I was comforted somehow by his short stature. He seemed less intimidating when I could only see an inch of his face.

The anesthesiologist sat by the boy’s head monitoring his vital signs. Everyone else took up their position. Nurses rolled up metal instruments. The videographer filmed, I watched. Only a small area of the boy’s abdomen was exposed – he could have been anyone.

I thought about what was happening in room 1503 that morning. I think about the mom saying goodbye to her husband. I hope she was less scared. I think about the son and the mother being wheeled on two gurneys into the operating room. Did they say goodbye? Against the wall in the surgical suite, wearing the equivalent of a shower cap, I start praying for them. For success today for the two operations. And for the doctor, this doctor who has been so hard on me.

Someone turns on a radio and the song, “Heard it through the Grapevine,” comes on. The energy in the room is a little peppy, especially for 6 am. I bend my knees up and down slightly in time with the song. I can see what is happening mostly by seeing the incision site from a television screen posted above the patient.

The doctor asks for an instrument from a nurse. I expected a lot of blood, but he makes the incision with an instrument that burns the edges of the wound as it cuts to stop the blood vessels from bleeding. Then he uses a little vacuum like the one used in a dentist ‘s office to suction out blood.

The videographer moves around the room capturing the action. I take a few pictures of the tray of instruments, the group of healthcare professionals in green, their heads clustered together. One nurse gives out the instruments. They count the number of sponges going in and coming out. The anesthesiologist reports vital signs. The doctor gives instructions with a light affixed to his head like a spelunker. It flashes inside the patient’s body cavity when he looks down and lights up the wall when he looks up.

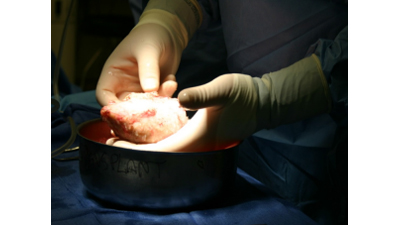

Another surgeon comes in to tell us that the living donor’s kidney is ready. The videographer and I go to the operating room next door. The other surgeon carefully cuts the veins and ureter from the donor’s kidney and removes the kidney from her body. The kidney is only the size of my fist. The doctor puts the kidney in a small bowl of ice and rinses away all the blood. The kidney is pink, then after a few minutes after the blood is rinsed away, it fades to white. I take a picture of it in the bowl of ice.

I ask the doctor if everyone’s organs look the same, no matter their race. “We are all the same color inside,” he says.

We return to the other operating room. My surgeon takes the white, chilled kidney out of the ice and sews its vessels into the bladder. The kidney starts filling up with blood again, slowly. Twenty minutes pass. “See, see,” he says, gesturing back to me over his shoulder, “come closer. It is getting pink. Now wait.” And, we do, looking down together, shoulder to shoulder, sharing the sterile field. When the kidney starts making urine, he tells me, “her son now has a functioning kidney.”

He looks over at me with smiling brown eyes. My eyes are teary. I think I am in love with this surgeon.