Written by Martha Gershun, Guest Blogger

When I donated a kidney to a woman I read about in the newspaper in 2018, the idea that xenotransplantation might someday make human organ donations obsolete was a far-fetched fantasy. Today, just seven years later, that fantasy is much closer to reality.

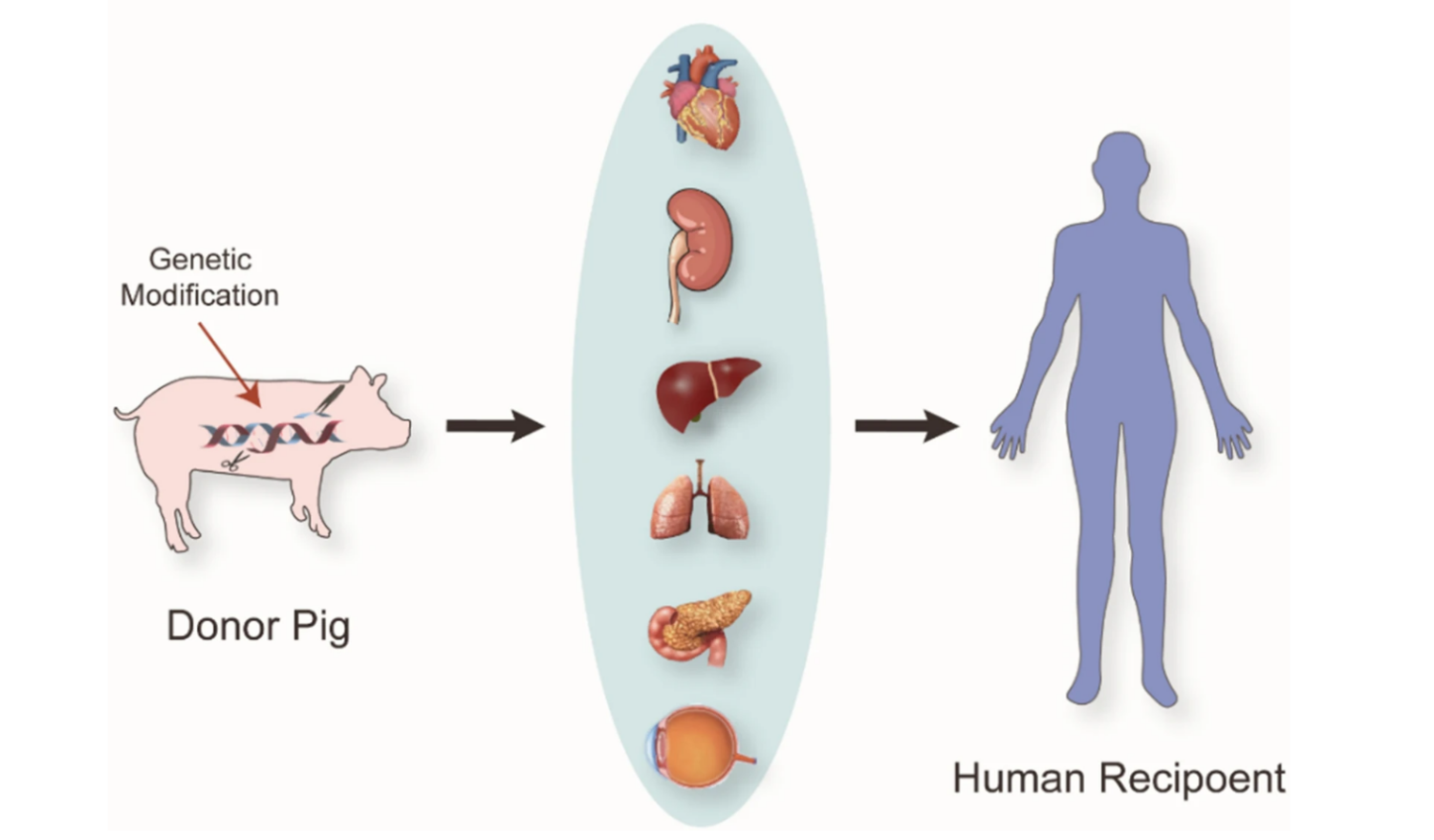

The first successful animal-to-human kidney transplant took place one year ago at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, when surgeons transplanted a kidney from a genetically-modified pig into 62-year-old Richard Slayman, who was suffering from end-stage renal disease. Slayman had received a cadaveric human kidney in 2018, but it had failed five years later. The pig kidney he received was provided by eGenesis of Cambridge, MA. The donor pig had been genetically-edited using CRISPR-Cas9 technology to remove harmful pig genes and add certain human genes to improve its compatibility with humans. Additionally, scientists inactivated retroviruses in the pig donor that are common to the species to eliminate the risk of infection in humans.

The surgery was successful, and Slayman was discharged from the hospital. Unfortunately, he died two months later, though MGH reported they saw no indication his death was a result of the transplant.

There have been three subsequent pig-to-human kidney transplants, two at NYU Langone Hospital in New York and one more at MGH. Two of those patients have died, however Towana Looney, a 52-year-old woman from Alabama who received a pig kidney at NYU Langone in November 2024, has returned home, where she continues to do well; she is now the longest-living recipient of a pig organ.

In February the FDA gave two biotech companies approval to begin clinical trials for genetically modified pig kidney transplants. United Therapeutics Corp. plans to enroll six patients in their trial, eventually expanding to as many as 50 people. Trial participants will need to be between the ages of 55 and 70; have been on dialysis for at least six months; and be deemed unable to receive a human donor kidney for medical reasons (likely because they are highly-sensitized to human HLA antigens) or unlikely to receive a deceased donor transplant within five years.

eGenesis will begin their study with three patients, with a similar option to expand. Their study participants must be patients who are living with kidney failure and unlikely to receive a human donor kidney within five years.

Researchers have focused on pig organs because they are similar in size and function to human organs. Pigs also have large litters and are easy to breed, which would make it practical to perform pig-to-human transplants at scale if the clinical trials are successful. Clinicians do not expect significant ethical arguments against the procedure as porcine heart valves have been used to replace human heart valves for more than 60 years. They account for a significant portion of the 250,000 heart valve replacements performed annually around the world.

Xenotransplantation has moved very quickly in the past year, and the ongoing survival of one of the earliest pig kidney recipients is very heartening. Still, it will be years before the clinical trials are completed.

Xenotransplantation trials are an “exciting step forward,” according to nephrologist Andy Howard, chair of the Kidney Transplant Collaborative, a nonprofit advocacy group that seeks to increase the number of kidney transplants in the United States. Speaking to Healthcare Brew on March 14, 2025, Howard notes that other options – such as living kidney donations – are a more realistic path right now. “While this innovation holds promise, widespread clinical use is likely at least a decade away, and patients on the waitlist don’t have that kind of time,” he said.

For now, patients with kidney disease remain reliant on the altruism of deceased donors and their families and those able and willing to become living donors to provide the lifesaving gift of a kidney transplant.

Martha Gershun is a nonprofit consultant and writer living in Fairway, KS with her husband Don Goldman. Her most recent book, Kidney to Share (Cornell University Press, 2021), with co-author John Lantos, MD, details her experience donating a kidney at the Mayo Clinic to a woman she read about in the newspaper. Gershun serves on the Expert Advisory Panel for the Kidney Transplant Collaborative and serves on the Board of the National Kidney Foundation Serving Kansas, Oklahoma, and Western Missouri.